Let’s say your favorite surf forecast app is showing 2–3 ft waves at your local beach tomorrow. But you check the offshore buoy, and it’s reporting an 8 ft swell at 11 seconds. What gives? Shouldn’t that translate to bigger surf at the beach?

Here’s what’s really going on—and why surf forecasting is a little bit science, a little bit art, and a little bit guesswork.

Shoaling: Why Waves Usually Get Bigger#

As deep-water swell moves toward the shore and hits shallower water, it slows down, the wavelength shortens, and the wave height increases. This process is called shoaling, and it’s why most waves grow in size as they approach land.

An 8 ft open-ocean swell with an 11s period carries a lot of energy. In ideal conditions—good angle, clean bottom contours, and no wind interference—you’d expect that energy to turn into significantly larger waves at the beach than what’s seen in the deep water.

So why would a surf report only call for 2–3 ft?

Why Waves Might Get Smaller Instead#

Even though shoaling usually amplifies swell energy, several factors can decrease or dilute it before it reaches your beach:

1. The Swell Direction Doesn’t Line Up with Your Beach#

In our example, the swell is coming from way south—let’s say 190°. If your beach break faces west or northwest, the swell might be approaching at an angle that misses the beach entirely, or just glances it. This is called swell shadowing or poor exposure.

Some of that energy might wrap in, but it’ll be weaker than if the beach faced directly into the swell.

2. Obstructions or Islands Block the Swell#

Depending on your location, offshore islands, headlands, or underwater terrain might block or scatter the swell energy before it reaches your break.

3. Local Bathymetry Doesn’t Amplify#

Some beaches naturally focus and amplify incoming swell (like reefs or points). Others, especially broad, flat sandbars, may cause waves to lose shape and power, especially at high tide.

4. Tide and Wind Interference#

Even if the swell has energy, onshore winds or bad tide timing can keep waves from standing up properly. If the tide is too high, it might just roll through the lineup without breaking at all.

5. Surf Forecasting Apps Make Assumptions#

Forecasting apps do their best to estimate how offshore swell will translate into breaking waves at a specific beach—but they rely on models and assumptions about swell direction, local bathymetry, wind, and tides. Sometimes they get it wrong. A 2–3 ft prediction might be overly conservative, or it might reflect realistic conditions if the swell angle or tide makes most of the energy miss your break.

Bringing It All Together#

So let’s revisit our scenario:

- Buoy: 8 ft @ 11s

- Forecast: 2–3 ft

- Swell Direction: ~190° (south)

- Local Break: Faces NW

Here, the swell has good energy (11s is plenty), but the southern direction is not ideal for a NW-facing beach. The forecast model likely accounts for this and assumes that only a fraction of that 8 ft swell will reach the shore with enough focus to form ridable waves. Hence the 2–3 ft projection.

But if your beach is tucked into a corner, blocked by headlands, or just poorly oriented to that swell direction—the waves might even be smaller than forecasted.

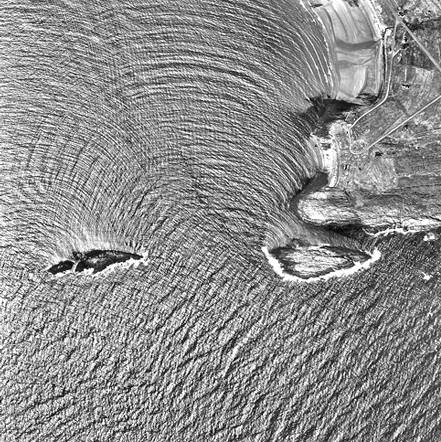

A Real-World Example: Island Refraction#

Here’s a perfect example of how swell can behave in complex ways: When south swell (190°) encounters an island, it doesn’t simply get blocked—it can actually wrap around the obstacle. The swell lines bend around the island’s edges through a process called refraction, potentially reaching beaches that don’t directly face the swell direction.

In this case, even though the beach faces north (opposite to the swell direction), some wave energy still makes it to the beach by wrapping around both sides of the island. However, this refraction process spreads out the wave energy, typically resulting in smaller waves than what the original swell might suggest. This is exactly the kind of scenario where an 8 ft @ 11s south swell might only produce 2-3 ft waves at a north-facing beach.

Bottom Line#

Waves usually grow as they move from deep water to shore, thanks to shoaling. But if the swell angle is off, the local geography doesn’t help, or wind/tide get in the way, you might end up with much less than the buoy suggests.

The forecast is just a best guess. The more you understand how your spot reacts to different swell directions, the better you’ll get at spotting when a forecast is off—and when it might actually be firing, even if it doesn’t look like it on paper.